- Home

- Simon Mayo

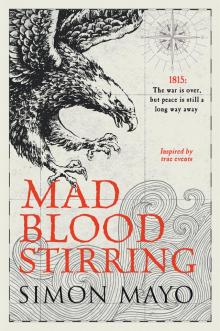

Mad Blood Stirring

Mad Blood Stirring Read online

About the Book

On the eve of the year 1815, the American sailors of the Eagle finally arrive at Dartmoor prison; bedraggled, exhausted, but burning with hope. They’ve only had one thing to sustain them – a snatched whisper overheard along the way:

The war is over.

Joe Hill thought he’d left the war outside these walls, but it’s quickly clear that there’s a different type of fight to be had within. The seven prison blocks surrounding him have been segregated; six white and one black. As his voice rings out across the courtyard, announcing the peace, the redcoat guards bristle and the inmates stir. The powder keg was already set to blow and Joe has just lit the fuse.

Elizabeth Shortland, wife of the Governor, looks down at the swirling crowd from the window of her own personal prison. The peace means the end is near, that she needn’t be here for ever. But suddenly she cannot bear the thought of leaving.

Inspired by a true story, Mad Blood Stirring tells of a few frantic months in the suffocating atmosphere of a prison awaiting liberation. It is a story of hope and freedom, of loss and suffering. It is a story about how sometimes, in our darkest hour, it can be the most unlikely of things that see us through.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Principal Players

Historical Note

Epigraph

Maps

Prologue: April, 1815

Act One

1.1: New Year’s Eve, 1814 Dartmoor, England

1.2: The Market Square, Lower Gates

1.3: The Market Square

1.4: The Physician’s House

1.5: The Market Square

1.6: Block Seven

1.7: Block Four, Cockloft

1.8: Block Four, Cockloft

1.9: The Agent’s Study

Act Two

2.1: Monday, 2 January 1815 Block Four

2.2: Dartmoor Hospital

2.3: The Market Square

2.4: The Market Square

2.5: Block Seven, Cockloft

2.6: Block Four

2.7: The Agent’s House

2.8: Block Four

2.9: Block Seven

2.10: Block Six

2.11: The Agent’s Study

Act Three

3.1: Friday, 6 January The Blocks

3.2: Dartmoor

3.3: Wednesday, 11 January Block Four

3.4: Tuesday, 17 January Block One

3.5: Saturday, 11 February Block Four

3.6: The Blocks

3.7: Sunday, 12 February Block Four

3.8: Block Four, Cockloft

3.9: Block Seven

3.10: Outside Block Six

3.11: Block Four, Cockloft

3.12: Block Four, Steps and Courtyard

3.13: Block Four, Cockloft

3.14: Block Four, Courtyard

3.15: The Hospital

3.16: Monday, 13 February Dr Magrath’s Study

3.17: Block Four, Cockloft

3.18: Tuesday, 14 February The Market Square

3.19: The Agent’s Study

Act Four

4.1: Friday, 17 March Block Four

4.2: Block Four

4.3: Block Four

4.4: Block Seven

4.5: Block Six

4.6: The Hospital

4.7: Block Four, Cockloft

4.8: Block Four

4.9: The Agent’s Study

Act Five

5.1: Friday, 24 March

5.2: Monday, 27 March

5.3: Saturday, 1 April The Agent’s House

5.4: Block Four

5.5: Block Four, Cockloft

5.6: Wednesday, 5 April The Agent’s House

5.7: Thursday, 6 April Block Four, Cockloft

5.8: Block Six

5.9: Block Four

5.10: Block Six

5.11: Block Four, Cockloft

5.12: Block Four

5.13: Block Six

5.14: Block Four

5.15: Block Six

5.16: Block Four, Cockloft

5.17: Block Four, Kitchens

5.18: Block Four, Ground-floor Hallway

5.19: Outside Block Seven

5.20: Block Four, Cockloft

5.21: Block Four, The Kitchens

5.22: Outside Block Seven

5.23: Block Four

5.24: Block Seven, Retaining Wall

5.25: Block Four, Cockloft

5.26: The Market Square

5.27: The Barracks

5.28: The Back of Block Six

5.29: The Courtyard

5.30: The Market Square

5.31: Magrath’s Office

5.32: The Market Square

5.33: The Market Square

5.34: The Market Square

5.35: The Agent’s Study

The Dartmoor Massacre

Author’s note

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

Dedicated to the memory of prisoner number 3154 and prisoner number 6520

Principal Players

The Americans

King Dick, sailor

Habakkuk (Habs) Snow, sailor

Sam Snow, sailor and cousin to Habs

Joe Hill, sailor

Will Roche, sailor

Ned Penny, sailor, lamplighter

Horace Cobb, sailor and leader of the Rough Allies

Edwin Lane, sailor, Rough Ally

Tommy Jackson, sailor, prison crier

Jon Lord, sailor

Robert Goffe, sailor

Alex Daniels, cabin boy

Jonathan Singer, cabin boy

John Haywood, sailor, lamplighter

Pastor Simon, reverend

The British

Captain Thomas Shortland, Agent, Governor of Dartmoor Prison

Elizabeth Shortland, Captain Shortland’s wife, assistant to Dr Magrath

Dr George Magrath, physician at Dartmoor

Martha Slater, market trader

Betsy Wade, market trader

Alice Webb, seamstress

Historical Note

The novel is based on historical events …

Since 18 June 1812, America and Britain have been at war, fighting what some will call the Second War of American Independence. It has already cost the lives of twenty thousand men. Much of the fighting has been at sea and, by the end of the war, on Christmas Eve, 1814, seven thousand American sailors are incarcerated in Dartmoor Prison, recently built for French prisoners taken in the war against Napoleon. Isolated and forbidding, it is the most feared prison in the land.

‘And if we meet we shall not ’scape a brawl,

For now, these hot days, is the mad blood stirring.’

Romeo and Juliet, Act 3, Scene 1, William Shakespeare

‘England being now at war with their own country … made them PRISONERS OF WAR, and close prisoners of war: shut them up in a close prison, on a bleak and naked down in Devonshire, called Dartmoor, in which prison we shall by-and-by see that some of them were killed on a charge of “MUTINY”.’

William Cobbett, MP, radical journalist and author, History of the Regency and Reign of King George the Fourth, 1830–34

Prologue

April, 1815

THERE IS JUST one hymn left to practise. But already every member knows every note, every breath between, each rise and fall. Pastor Simon stands to conduct, but the choir is already singing. Most have their eyes closed; all of them are swaying.

‘Farewell, dear friends, a long farewell,

Since we shall meet no more,

Till we shall rise with thee to d

well

On heaven’s blissful shore.

We will meet you in the morning,

Where the shadows pass away;

We will meet, we will meet,

Where all tears are wiped away.

Our friend and brothers, lo! are dead,

Their cold and lifeless clay

Has made in dust its silent bed,

And there it must decay.’

A giant of a man steps forward, his arms wrapped around himself for comfort, for support. He has been crying but, eyes screwed tightly shut, he is determined to lead the last verse.

‘Farewell, dear friends, again farewell;

Soon we shall rise to thee,

On wings of love our stars will cross

Through all eternity.’

There is a moment’s silence, a beat’s pause as the final note dies. At first, no one moves. Then, as if emerging from a trance, the choir disperses, some of them still humming the melody as they clatter down the stone steps and wander out into the April rain.

1.1

New Year’s Eve, 1814

Dartmoor, England

THE TWELVE AMERICAN sailors, starving, filthy, exhausted, who had been stumbling across the frozen moorlands since first light, regarded their well-fed and well-armed British captors, dressed smartly in bright red tunics, and concluded it was time for revenge.

They started to sing.

Full-throated and tuneless, the surviving men of the Eagle drove the guards of the Derbyshire militia crazy.

No one sang here, not ever.

‘Will you ever shut up?’ snapped one soldier, his unshaven face purple with rage and cold. He swung his rifle towards the prisoners, its bayonet missing one man only by inches.

‘Let them sing!’ called out another. ‘When they see where they’re heading, they’ll be quiet soon enough.’

‘And by the time they see the sun again,’ called a third, ‘the bloody pox will have taken their voices, anyway!’

The four soldiers laughed.

The small squadron trudged further up the hill, the narrowing track forcing the prisoners into six shuffling rows of two. The wildly uneven path, at best nothing more than trampled-down gorse littered with rocks, picked its way across featureless hills, the occasional dilapidated farmstead the only sign of human habitation. Many of the Americans had difficulty walking; arms had been linked and shoulders grasped. They were poorly dressed for the march and the bone-chilling cold. A few had boots, but the rest slipped and fell in their canvas shoes. A variety of hats were on display, some barely more than a square of tarpaulin tied in place with rope, but one stood out. At the back of the parade, one prisoner sported a three-cornered felt hat, pulled low over his brow, a few inches of closely cropped blond hair showing beneath its brim. He looked no more than sixteen. A tattooed eagle, wings splayed, bill and talons slashing, was just visible above his collar, roughly inked at the base of his skull. He leaned towards his marching companion.

‘Woman back at the dosshouse said it was fifteen miles,’ he said. ‘And seeing as that feels like at least thirty miles back, it can’t be far now, Mr Roche.’ He used both hands to steer the older man around a vast, rain-filled pothole.

‘You sure that’s what she said, Mr Hill?’ said his companion. ‘I didn’t understand a goddamn word she said.’

Joe Hill snorted. ‘Maybe you weren’t listening, Mr Roche. It’s Devonshire talk, that’s all. Just Devonshire talk. She thought we were renegade English and that we’d lose the war for certain. That it was a right impertinence for America to fight England again. We deserved jail is what she said.’

Will Roche spat in the mud, strands of phlegm sticking in the whiskers of his straggly beard. ‘She knows nothin’ of our fine Yankee victories then,’ he said. ‘Renegade English? For shame.’

‘Well, I reckon she’ll find out soon enough,’ said Joe. ‘We have proper American news, Mr Roche. American news fit for Americans, and there’s plenty where we’re heading. Might even know some of ’em.’

Roche’s voice dropped a little, flickers of tiredness and doubt licking at his words. ‘And you’re sure about this, Joe? You’re sure ’bout what you heard? ’Cos if we’re stayin’ in Dartmoor, we might as well make a run for it now. I’d rather die in one of these frozen ditches than be tortured by some English ass-worm.’

Joe put both his hands on the older man’s shoulders, his grip firmer than his narrow shoulders suggested. He spoke with all the assurance he could muster.

‘I heard what I heard, Will,’ he said. ‘My ears might’ve taken a beating these last years, but those words I heard true and clear. So, yes, I’m sure. You’re the father of the ship now. You should be sure, too.’

He hummed a few more bars and Roche nodded, momentarily reassured. Joe knew that Roche had always enjoyed hearing him sing, his shanties and songs of home always a welcome part of their life at sea. Since their capture, however, there had been silence. Joe had seen no reason to sing, no reason to dress their despondency with music, but now the tunes came again. Now, there was a purpose and a plan.

‘We mustn’t let them English think they’ve got us beat,’ he said. ‘They think this is their triumph, their victory. Well, they’ve got a surprise coming.’

Joe didn’t smile – it wasn’t his way – but any shipmates listening heard his excitement, sensed his buoyant mood. They knew his secret, and it helped to keep the gloom at bay.

The fog rolled away, blown by some unfelt zephyr. They had been climbing since first light, but this was no vantage point, just an endless, rotting-brown wasteland, a panorama as bereft and cheerless as a desert. Joe fought against the chills.

‘If it wasn’t for the hallelujah in our hearts, Mr Roche,’ he observed, ‘we might conclude this is the arse-end of England.’

‘We might indeed,’ said Roche. ‘And looks like we’re ’bout to climb right into it.’

Up ahead, the redcoats conferred, then steered their prisoners from the track towards a steep escarpment. As Joe scrambled past, two of them smirked at him. ‘’Ope you’re not goin’ to stop singin’ now,’ said the purple-faced one. ‘Not now you’re so nearly ’ome.’ They laughed, then the purple one coughed and spat. The path they indicated was wider and less marshy, but the gradient was a tough one and the English knew it.

‘What was wrong with the other track?’ asked Joe.

‘View’s better this way,’ said the purple soldier.

‘Proper scenic it is,’ sneered his colleague. ‘Quite something, top of this ’ere hill. All the prisoners say so.’

The sailors’ exhaustion was now bone-deep. Painful, bloodied feet began to slip from underneath tired bodies as they climbed, weary hands reaching out for balance. Leaden legs cramped then gave up altogether. Joe put both hands on the sodden, muddy hips of the barrel-shaped man in front of him, and pushed.

‘Steady, Mr Goffe,’ he said. ‘You don’t want to stay here, you’ll miss the party. We’re nearly there.’

There was a pained grunt from the man ahead. ‘There’d better be a goddamn party,’ he growled.

Joe recalled those miraculous harbour-side words he’d overheard just a few hours ago. The smiles. The back-slapping. The toast. Surely there could be no mistake.

‘There’ll be a party all right,’ he muttered.

The summit was marked by a solitary, skeletal pine tree, and a militiaman sitting beneath it stood to greet them, his arms open wide. ‘Welcome to Dartmoor,’ he beamed. ‘Why don’t we rest your rotten Yankee bones here for two minutes, just so you can take it all in, like.’

Joe clambered his way over the top, pushing Goffe then pulling Roche as he went. Around him, the cursing told him everything he needed to know. This wasn’t the casual profanity that was part of a sailor’s life; this was fearful, terrified blasphemy.

‘Sweet baby Jesus, would you look at that!’

‘Christ alive!’

Across the fields – another half-mile of gorse and stones

– a great prison city had been carved from the moor. A huge encampment of enormous grey hulks, vast granite buildings with pointed roofs shunted hard together, seemed to grow from the earth. There were turrets, chimneys, fences and, surrounding the whole, two formidable encircling walls. All of it was grey. A deathly, exhausted, pain-filled grey. An unearthly silence seemed to spread across the fields, reaching out from the prison to envelop the sailors.

‘What in God’s name?’ muttered Joe, dread settling deep in his stomach. ‘It’s a ghost town, a goddamn ghost town.’

‘And we’re the goddamn ghosts,’ said Roche.

Joe was aware of Roche’s hand gripping his arm.

‘There ain’t no windows,’ said Roche.

‘What?’

‘No windows. None.’ There was real fear in the old man’s voice. ‘Look at ’em, Joe, tell me I’m wrong.’ Joe stared at the largest buildings; he counted seven in all. At first glance, they did appear to be solid, relentless walls of brick. But then his eyes adjusted and he picked out some detail that had been lost in his first, shocked sweep of the prison: rows of tiny squares ran like gun ports across the length of each wall.

‘You’re wrong, Will. There’s windows, all right, just not so big as any light’ll get in.’ He felt Roche sag against him. ‘What was it you used to tell me?’ he continued. ‘“Tribulation worketh patience; and patience, experience; and experience, hope.” That’s what we need. Patience and hope, Will. Now more than ever.’

‘I said that?’ said Roche.

‘You said that.’

‘Must have been in my cups then. Sounds like a crock o’ shit to me.’

‘Really?’ said Joe, surprised. ‘Well, seeing as we’re not going to be staying long …’

He began to whistle. He forced it to begin with, his mouth dry and his heart heavy, but its effect was instantaneous. The melody of ‘Yankee Doodle’ worked a little magic of its own. Hunched backs straightened, shoulders squared, eyes lit up. It was musical insubordination. By the end of the first verse, twelve sailors were whistling in unison. By the end of the second, they had fallen into line and begun their own, voluntary march to the prison, the soldiers cursing and scrambling to keep up.

Blame

Blame Itch Rocks

Itch Rocks Mad Blood Stirring

Mad Blood Stirring Itch

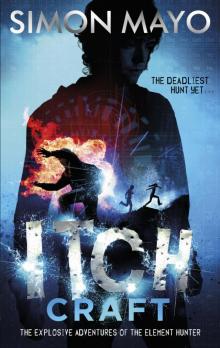

Itch Itchcraft

Itchcraft