- Home

- Simon Mayo

Blame

Blame Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Speaking in Spike: Some Prison Slang

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Simon Mayo

Copyright

ABOUT THE BOOK

Heritage crime [noun]: A previously undetected crime committed by your parents or grandparents for which you are held responsible.

Ant and her brother, Mattie, are locked up in Spike, a new family prison.

Society demands they do time for the unpunished heritage crimes of their parents.

Tension is simmering inside the jail.

When the tension breaks and a riot begins, Ant realizes they’ve got one chance to break out.

It’s time for Ant to show the world that they’re NOT TO BLAME.

Dedicated to prison reformers everywhere, campaigning for those who are not to blame

SPEAKING IN SPIKE: SOME PRISON SLANG

Ant Abigail Norton Turner

Basic Removal of privileges

Bax Go away

’Bin Cell – short for cabin, the cells of the Spike

Bingo A riot

Bug group Resistance group (from German Bug meaning prow, strut)

Castle Holloway Prison

Collar A strutter parent on day release, allowed to work with their wages paid to the state so as to repay their debt to society sooner

Cons Convicts; what strutters call all non-strutter prisoners

Dixam pas Leave us alone

Doing a six Serving a six-year sentence

Ghetto penthouse Top-floor cell

Happy Hour The hour before Correction

Heritage crime A previously undetected crime committed by your parents or grandparents for which you are held responsible

Hunchies Non-strutters

IR/Indoor Relief Prison-organized work

Jammer Home-made knife

Jug up Meals

Ladies/Ladies of the Castle Prisoners in Holloway

Molopaa Dickhead

Na Hey! How are you?

Naa Hey! Good, and you?

Pat down Body search

Pol-drone Police drone

POs Prison officers/guards

Rub down Cell search

Screws Prison officers

SHU/bloc/box Single Housing Unit – solitary confinement

Solo A strutter in prison without any family

Spike The family wing of Her Majesty’s Prison London

Spikeout On release or escape from HMP London. Anything that is ‘outside’

Strap/handle The tag worn by strutters

Strutter Someone found guilty of heritage crime. The term comes from the altered posture and gait of those wearing the plastic and steel tag, placed in the small of the back

Village Pentonville

Villagers Prisoners in Pentonville

The secret of a great fortune made without apparent cause is a crime that has never been found out, because it was properly executed.

Honoré de Balzac, Revue de Paris

No one has locked up families before. I can’t think what took us so long.

Assessor Grey, HMP London

The girl with the pudding-bowl haircut crawled out of her bedroom, edging her way to the banisters. She lay flat on the carpet and peered down into the hall. She watched as a white man in a smart coat half steered, half carried a black woman through the open front door. She heard the opening and closing of car doors and, behind her, the shuffling of her brother’s small feet.

‘Get down,’ she said, and he lay next to her, copying her exact pose, pushing his face against the white wooden slats. He too had a straight fringe, the rest of his hair cut to the same length. They looked at the packed suitcases, some bursting with clothes which had spilled out onto the tiled floor.

‘Are they going away again?’ he whispered.

‘Looks like it,’ she muttered.

‘Where are they going?’

He felt her shrug.

They both tensed as they heard their father walking back from the car. He strode into the hall and scooped up the piles of loose clothing, shoving them into one of the suitcases. He disappeared through the door again, and the girl realized he would return just once more to pick up the two remaining cases. Then they would be gone.

Hardly breathing, they heard his every step. They heard him curse their mother, heard the thud of the cases as he threw them in the boot, heard him humming an old hymn tune as he walked back to the house.

‘He’s happy,’ whispered the boy.

‘He’s drunk,’ whispered the girl.

He stood in the doorway and looked around, a man unmistakably taking his leave. He caught sight of his children staring at him from the landing, and froze.

The girl and the boy froze too, breath held, hearts pounding.

She wasn’t sure how long this moment lasted, but when he eventually stepped inside, her chest was bursting.

The man picked up the cases, looked once more at his daughter and then at his son.

‘You’ll be fine,’ he said, then turned and walked out of the house.

She knew she was late and she knew she was in trouble.

She’d feasted on double cheeseburger and fries: beef, pickle, Monterey Jack cheese, bread, ketchup, fried onions.

She’d also enjoyed the café’s wifi; trawling and posting on all the banned sites she could find.

And the final treat – she’d even managed a few minutes hidden in her old garden, staring at her old house. Her fake ID, debit card and phone were safely buried back there too.

Everything had been timed, every moment of freedom accounted for, but these boys had messed it all up. Whateve

r the reason for their delay, Ant now needed to hurry. She was beginning to worry that she’d missed them altogether when, finally, she heard them coming.

There were just two of them, both rangy, loud and full of swagger. She didn’t need her vantage point behind the stinking industrial-sized bins – you could have heard their bragging streets away. She felt the steel handle of the bin lid in her hand and crouched lower.

The two Year Ten boys strolled down the cut-through to the park. Ant’s whispered count was to four, the numbers spoken instinctively in her Haitian Creole.

En, de, twa, kat.

She stepped out into the alley. In six silent paces she was behind them, in step, grinning. This was her favourite part, the anticipation. This is what she did, and it felt good every time. Her agitation and six-o’clock deadline forgotten, she pulled her hood over her shaved head and leaned in close.

‘And what have you done today?’ she hissed.

The boys whipped round and a wall of steel hit them. The crunching sound of metal on bone rang through the alley and they dropped like stones, hitting the tarmac hard. One was out cold; the other rolled around clutching his bleeding nose. Eyes wide, he tried to scuttle backwards, to put some distance between him and his attacker.

And then she was on him. Sitting on his chest, she placed a hand on his broken nose and pressed. If her other hand hadn’t been over his mouth, he would have howled. He tried to punch and kick her off, but she pressed harder and he stopped.

She leaned forward till her mouth was next to his ear. ‘I said, what have you done today?’ She watched as he tried to work out what he was supposed to say. His eyes flitted over her, and she saw him recoil. Ant smiled; it wasn’t her goose tattoos that had made him react.

‘I know . . . a girl! And a halfie too! Under all that blood, I actually think you’re blushing.’ Keeping one hand on his nose, she edged up his chest. She knew she was taking too long and forced herself to speed up. ‘Last time: what have you done today?’

The boy finally found words. ‘Dunno what you mean!’ he shouted. They came fast now. ‘Been at school, haven’t I? You want my timetable or something? ICT, maths, English, all that stuff. You’re like that advert . . .’

Hurry up, Ant.

She pressed down again and he squealed. ‘You have French today?’ He nodded. ‘Were you a good boy, Sean? Did you behave?’

The boy combined horror that this crazy girl knew his name with a frantic nod.

‘So you didn’t call your teacher “strutter filth” like you did yesterday? And you didn’t threaten his family like you did yesterday? And you didn’t cut his clothes like yesterday?’

Really hurry up, Ant.

With her free hand, she felt in all his pockets. She found the knife and held it dangling from her fingers.

‘You take it!’ he gasped. ‘It’s not mine anyway.’ The knife disappeared into her hoodie and she leaned forward again till her face was right above his. She could smell cigarettes and chocolate.

‘Thanks. I’ll find a safer home for it.’ She pressed down on his nose and felt him arch beneath her. She was whispering now. ‘And if you ever threaten Mr Norton again, I’m coming straight back to find you and your pathetic friend.’ She nodded at the other boy, who was still out cold. ‘Clear?’

Sean nodded furiously. She lifted her bloodied hand and wiped it on his T-shirt.

‘So, what have you done today?’

‘Nothing. Done nothing.’

‘Good boy.’

Now run, Ant.

She ran.

She threw the knife into a bin as she passed and heard the boy shout, ‘You’ll go to prison for that!’ And even though she knew she really shouldn’t, she turned round and sprinted back. She knelt down again.

‘That’s the whole point, Sean. I’m already there.’

As she ran out of the alley, Ant cursed herself. The job was done, but she had always known how long she could be out for; known when she had to be back. And she had blown it. Anyone who saw Abi Norton Turner run for the Underground station knew that she wasn’t merely in a hurry – everyone in London was in a hurry; she was in danger. There was a mania to the way she tore along the street. Her eyes were fixed on the traffic lights, calculating light changes and gaps in the crowds. She yelled at anyone who was, or might be, in the way. Most froze when they saw her coming, a few edged aside. One oblivious headphone-wearing tourist was sent sprawling as he stepped into her path, her free hand hitting his shoulder hard. There were no apologies, no glances back. Ant barely heard the curses that were hurled her way. A memory of her kid brother alone in his cell, bruised and miserable, came to her.

Not separation. Not this time.

When the pavements were too full, she took to the road. Using the gutter, she accelerated past the beggars and shoppers, some of whom watched her with alarm, instinctively glancing back down the street looking for a pursuer. Hers was the speed of someone running for her life.

She saw the red and white Underground sign. Two minutes to the platform, thirteen minutes’ journey time in total, on two trains, ninety seconds to the prison . . . It wasn’t possible.

A crowd of students wandered across the station entrance, then hesitated, apparently lost.

‘Out of the way!’ yelled Ant, sprinting across the road, her voice all that was needed to create a path to the steps. She took them three, four at a time, smacked her pass on the barrier and ran for the escalator. ‘Coming down!’ she shouted, and most of the commuters shuffled right to let her come by.

She jumped, squeezed and pushed her way down to a man with a buggy who blocked her way. He glowered at her, daring her to challenge him. She hesitated. Then, to the man’s astonishment, she climbed onto the moving handrail and tightrope-walked past him, then leaped for the ground.

A train was in – she could hear it. There’d be another in two minutes, but that would be two minutes too late. She rounded the corner – its doors were still open, but the beeping sound meant she had seconds before they slid shut. She cursed as she swerved past more slow-moving tourists but their vast trundling luggage briefly hemmed her in. In the split second it took her to side-step the cases, the train’s doors closed. She cursed again and tried to prise the doors open. On the other side of the glass, a teenager in a Ramones T-shirt dug his fingers into the rubber edges and pulled. The doors opened a few millimetres and Ant plunged her hand into the gap. She had some traction now, and between them, she and the Ramones fan edged the doors apart, forcing the driver to open them again.

Ant crashed into the Tube carriage. She ignored the stares from her fellow travellers – some irritated, others perturbed by this sweat-soaked crazy girl who had just joined them – and nodded her thanks to the Ramones guy.

She took great lungfuls of air, her chest heaving; then bent down, hands on knees. ‘Please stand clear of the doors,’ said the automated message, and Ant just had time to grab a rail before the train lurched away from the platform.

‘You in trouble?’ said the Ramones boy.

Ant, her eyes closed, nodded. She was grateful, but didn’t want a conversation.

‘You a strutter?’ he persisted.

Startled, she opened her eyes. A few passengers edged away from her, disgust etched on their faces. She flashed him a warning. The boy retreated and stared out of the window, but Ant was annoyed she’d been spotted.

Am I really that obvious? Even without the strap?

She had assumed that, free of her debilitating tag – currently in her brother’s bag – she would move just like anyone else. Then she felt the sweat pouring from her and answered her own question. It had nothing to do with how she was moving. If you were as desperate as this, two stops from the biggest new prison in Britain, then yes, you probably did look like a strutter.

The train was slowing, the platform sliding into view. Through the glass, Ant saw the crowds waiting to board her train and readied herself for the scrum.

Running was impossible

. As she jumped out of the carriage, she met a wall of travellers who weren’t about to get out of the way of a diminutive girl in a hoodie and trainers. She shoved, pushed and swore, but was moving at barely walking pace. With each hopeless half-shuffle she felt her brother fall from her grasp, her foster parents disappear. No Mattie, no Gina, no Dan. She had learned to pick her battles. Ant had thought that this revenge mission was small-scale. Achievable. Fair. She had been right too, but if she wasn’t back for inspection, then everything changed.

Desperation seeped into her mind. Do something drastic, do something crazy.

Ant screamed – a wailing banshee howl that made the whole platform stop and look. Those who could see her backed off as far as possible, and she screamed again. As this shriek was delivered to a near-silent station, the effect was dramatic.

A path cleared for her and she ran, taking the steps in enormous leaps. Where new crowds threatened her progress, she screamed again. Steps, escalator, sprint, Ant flew towards the Piccadilly Line. In the enclosed walkways that linked the Underground system, her yells and threats bounced off the tiled walls.

The platform was busy with the usual number of construction workers – all with their tell-tale prison security passes still visible – but she could still choose her spot. If she stood by that poster, she would be right outside the lifts at the next station.

She knew the poster well. It showed a troubled-looking man in an armchair being questioned by his two young children. The caption read: Daddy, what did our family do before the Depression? It then dissolved into a smiling suited man holding up a pledge card. Underneath a bold Your past is your future! were the five ‘Freedom Questions’.

Ant knew them by heart:

What have you done today?

Have you talked to your parents?

What have you inherited?

What are you passing on to your children?

Is your family now, or has it ever been, a criminal family?

If the ad hadn’t been on the wrong side of the tracks, she’d have thrown something at it.

As the sound of the approaching train filled the platform, she suddenly realized she wasn’t the only strutter in trouble. Never having done this trip so close to inspection, it had never occurred to her that she might have company. Ahead of her was a small group standing apart from the crowd. Or rather, the crowd stood apart from them.

Blame

Blame Itch Rocks

Itch Rocks Mad Blood Stirring

Mad Blood Stirring Itch

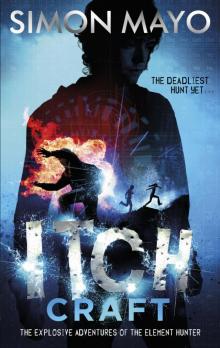

Itch Itchcraft

Itchcraft